By Dr. Julie Schell, Xie Hill, Tamie Glass, and Dr. Kelly Miller

COVID-19 has decimated decades of progress on the world’s most pressing social issues, including healthcare, poverty, hunger, reliable work, equity, and education (United Nations, 2020). The pandemic and its crescendo of human pain and suffering has put organizations working on behalf of marginalized communities in the midst of one of the wickedest problems of our lifetime. Design thinking, or human-centered design, offers opportunities to deliver social change, but only if people can—and choose to—use design to make an impact.

After spending precious, scarce resources (time, personnel, and money) on design thinking training and education, leaders – in the corporate and social-sector alike - too often find themselves in a predicament. Even with early signs of enthusiasm and affinity, design thinking is usually a short-lived intervention in organizations. This is because design thinking involves highly complex content that has a steep learning curve for non-designers. When the fanfare of a playful design thinking workshop wears off, most non-experts are left without the knowledge or confidence to execute on design thinking initiatives. To use design thinking effectively employees generally need to engage in practice, collaboration in a supportive, design-centric community, and time – all things that compete with bandwidth social sector workers need to dedicate to the people they serve.

Without ongoing support, local initiatives, and expensive design consultants, social service and corporate peers alike rarely realize the widespread uptake they hoped for with design thinking professional development. As a result, the wicked problems design thinking is well-suited to address fester in an expensive training-lack-of-adoption gap. Many people who sponsor design thinking trainings report, “we tried design thinking, but it just did not work here.”

Based on the large number of design thinking trainings available from the highest-caliber institutions, the proportion of design-centric organizations should be demonstrably higher than it is. While the best design educators work intuitively to deliver human-centered design for adoption, there is a shortage of evidence-based design thinking pedagogy to draw on to help ensure effective uptake. The purpose of this article is to report that, using the Pedagogy of Self-Efficacy in Design Thinking Education Framework outlined previously in this journal (Schell, 2018), we observed a statistically significant increase in design thinking self-efficacy among non-designers working on a serious, education-specific social issue. We propose that adopting this framework provides one evidence-based way to increase design thinking self-efficacy among non-designers working for social change. Furthermore, we argue that social change organizations looking for return on scarce investment resources should ensure any design thinking professional development initiatives have intentional and transparent self-efficacy learning outcomes.

Teacher Retention Design Thinking Studio

As designer and educator, respectively, two of this article's authors (Schell and Glass) began a yearlong project with one Texas school leader to test a theory of change related to this design thinking training-adoption gap. The district serves large percentages of marginalized students and sought intervention on a specific wicked problem: teacher turnover.

Pre-COVID-19, teacher turnover was a grave national problem. The teaching workforce still has not recovered from the 2008 economic crisis, and public school leaders faced a shortage of more than 100,000 teachers in elementary and secondary schools (Griffith, 2020). Outside of a recession, approximately 14 percent of teachers leave their schools annually, and in Texas the percentage is much higher, averaging 20 percent. With COVID-19, according to the Economic Policy Institute (2020), “more K–12 public education jobs were lost [in April 2020 alone] than in all of the Great Recession” (Kini, 2020).

Teacher departure has the most deleterious effects on low- or limited-resource schools. When a teacher leaves a low-resource school, it strains an already strained infrastructure—leaving students who most need upward mobility with inconsistent access to quality education. The negative impact of teacher attrition on student achievement harms students across schools, not just the students whose individual teachers leave. On the other hand, when experienced teachers stay, they can insulate economically disadvantaged students and students from marginalized groups from cycles of poverty and institutionalized racism that are perpetuated by educational inequity.

A Theory of Change Based on Design and Learning Science

With the consequences of teacher attrition looming, Schell and Glass merged their expertise in design and learning science to create a studio-based experience for training 153 public education teachers, principals and assistant principals, and district staff. They designed the studio to equip participants with two things:

- Skill in “unbundled” design thinking. As a process, Schell and Glass determined design thinking is too complex for new learners to immediately implement the standard process of empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test. As such, Schell and Glass teach new learners how to implement human-centered design methods independent of the more traditional 5-step process. The studio uses pedagogical scaffolding to ensure new learners can practice those more independent methods. Scaffolding is an educational approach whereby instructors add supports for learners at the beginning of a learning experience. In this studio, the supports are temporary and eventually removed so that the end of learning experience mirrors what it will be like to use human-centered design outside of the professional development context.

- The Pedagogy of Self-Efficacy in Design Thinking Education Framework originally outlined by Schell in this journal in 2018.

Self-efficacy is one of the single most influential determinants of human behavior and motivation. Bandura (1978,1997) defines self-efficacy as one’s belief in their ability to complete a domain-specific task. Self-efficacy researchers have demonstrated that if we believe in our ability to complete a task or activity in a particular domain, we are more likely to engage in that domain (Bandura, 1978,1997). If, on the other hand, we think we are inept in a particular domain, we will shy away from it. There are four specific sources that design thinking educators can use to build self-efficacy: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and physiological and effective states. Schell (2018) detailed specific activities and recommendations for developing design thinking pedagogy aligned with the four sources of self-efficacy.

The teacher retention studio employed unbundled design thinking and Schell’s framework to deliver design thinking instruction on the specific topic of teacher retention. We operated with the theory of change that an unbundled instructional approach that intentionally developed all four sources of self-efficacy would lead to increased design thinking self-efficacy among new learners. We expected, but did not measure, that greater design thinking self-efficacy might serve as an armor against abandoning design thinking post-workshop.

Sample and Method

The sample included 153 studio participants across three cohorts, consisting of school leaders, district administrators, and teachers working in a metropolitan school district in Texas. The lead instructors (Schell and Glass) were held constant, and each cohort participated in 18 hours of design thinking instruction spanning three days. As part of routine studio program evaluation, we used the Design Thinking Self-Efficacy Measure (Schell, 2020) (Appendix A) to evaluate design thinking self-efficacy before and immediately after the studio.

Relying on inferential statistics, we conducted paired t-tests to assess the following research question: How does studio participants’ self-reported self-efficacy change before and after an 18-hour studio designed intentionally to build design thinking efficacy among non-designers? Our next endeavor was to test the hypothesis that any change in participants’ design thinking self-efficacy was based on chance and was not statistically significant.

Results

On every item in the Design Thinking Self-Efficacy Measure, participants’ self-reported self-efficacy increased after participating in the studio. Using descriptive statistics, we measured the percent change from the average self-efficacy rating for all 153 participants before the studio and after on each item. The percent increases for each measure are detailed in Table 1. The responses to our research question demonstrated a positive increase in participants’ self-reported design thinking self-efficacy after the studio.

| Design Thinking Self-Efficacy Item | Average Score Before Studio (1–6) | Average Score After Studio (1–6) | Percent Increase | Statistically Significant at the .001 level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1. You know enough about design thinking that you can use it right now | 2.72 | 5.1 | 89.81% | * |

| Item 2. You can explain one way to use design thinking | 2.77 | 5.27 | 90.09% | * |

| Item 3. You could teach a peer to use design thinking in one way | 2.59 | 5.05 | 95.20% | * |

| Item 4. You can identify other people around you who use design thinking methods | 2.95 | 5.12 | 73.61% | * |

| Item 5. You can use design thinking in your work every day | 3.01 | 5.23 | 74.02% | * |

In response to the question of whether or not the change was statistically significant, we used inferential statistics to conduct paired t-tests. On every item, we determined the observed change was statistically significant at the P<001. In the world of data, this is remarkable because it means that there is less than one percent probability that the changes noted in Table 1 were due to chance or luck. To be clear, we did not evaluate or set up this evaluation to have any causal implications. While the data does not reveal that the workshop caused an increase in self-reported self-efficacy, the evaluation illustrates that before and after the 18-hour experience, participants’ self-reported self-efficacy increased in a manner that is very statistically significant.

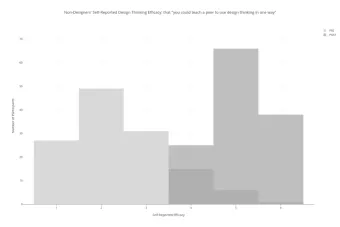

Figure 1 draws attention to Item 3 specifically, which measured participants’ confidence that they could teach a peer to use design thinking. We demonstrate this change in visual form because it was the highest percent increase observed. The light gray represents the pre-studio response and the dark gray, the post-studio response.

Implications

Based on our findings, we recommend merging the instruction of common design thinking methods with established learning science principles and frameworks—in this case, self-efficacy theory. We propose that using an evidence-based design thinking pedagogy may increase design thinking self-efficacy among non-designers, which has implications for future use and adoption of the method. As such, we endorse the adoption of a similar pedagogical approach by practitioners who aspire to use evidence-based design thinking instruction.

The result provided in Figure 1 is especially important because we believe that in order for design thinking to be adopted within organizations, people must be able to spread it through advocacy and teaching others. Although we have some anecdotal evidence to rely on, one limitation of the study is we did not empirically investigate if greater self-efficacy led to greater attachment to design thinking in the studio– an important research question for future work.

Nearly a quarter-century’s worth of empirical research literature demonstrates that self-efficacy is a determinant of future behavior. If non-designers do not gain design thinking self-efficacy during workshops or studios, the potential for widespread uptake and adoption is limited. Intentionally designing studios and workshops to build design thinking self-efficacy increases the potential that learners will adopt the method and use it in the future, beyond the situated studio or learning environment. If design thinking and human-centered design is to reach its potential as a beacon for social change, non-designers must be able to deploy it effectively and adopt it for the long term. With the impact of COVID-19 on nearly every marginalized group and social issue, we cannot rely on designers alone to enact change. We need to empower non-designers working for social change to adopt human-centered design methods to help the people they serve.

Appendix A

Design Thinking Self-Efficacy Measure (Schell, 2020)

Participants responded to the pre- and post-studio evaluations using five questions adapted from previous instruments developed and published by Miller and Schell (2015).

Think of a learned skill that you know you are really good at doing. For example—analyzing data, leading a team, creating a lesson plan, handling conflict, facilitating a meeting, or managing a budget.

This can be anything, just something you have a high level of confidence in. What is that skill?

Compared to the level of confidence you have in the skill you described above, how confident are you in the following areas:

Not confident at all

Not very confident

A little bit confident

Confident

Extremely confident

I don’t know what design thinking is

- That you know enough about design thinking that you can use it right now

- That you can explain one way to use design thinking

- That you could teach a peer to use design thinking in one way

- That you can identify other people around you who use design thinking methods

- That you can use design thinking in your work every day

Appendix B

Histograms of all pre-post studio results on the Design Thinking Self-Efficacy Measure

Item 1

Non-Designer's Self-reported Design Thinking Efficacy: on "knowing enough about design thinking that you can use it right now"

Item 2

Non-Designer's Self-reported Design Thinking Efficacy: that "you can explain one way to use design thinking"

Item 3

Non-Designer's Self-reported Design Thinking Efficacy: that "you could teach a peer to use design thinking in one way"

Item 4

Non-Designer's Self-reported Design Thinking Efficacy: that "you can identify other people around you who use design thinking methods"

Item 5

Non-Designer's Self-reported Design Thinking Efficacy: that "you can use design thinking in your work every day"

Acknowledgments

Julie Schell conceptualized, designed, and drafted the analytical approach and narrative for the paper. Xie Hill developed the data management approach and conducted the statistical methods. Tamie Glass co-designed the studio with Julie Schell and contributed to the narrative of the draft. Kelly Miller reviewed the statistical methods and results and provided consultation on the methods section. Cassidy Browning and Edgardo Irizarry contributed substantive studio design support. The superintendent of the district participating in the studio provided input and permission to publish this article.

References

United Nations, 2020 https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

Kini, 2020 https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/covid-raising-demands-reducing-capacity-educator-workforce

Nguyen & Springer, 2019 https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2019/12/04/reviewing-the-evidence-on-teacher-attrition-and-retention/

Schell, 2018 https://designcreativetech.utexas.edu/design-thinking-has-pedagogy-problem-way-forward

Schell & Miller, 2015 https://scholar.harvard.edu/kellymiller/publications/response-switching-and-self-efficacy-peer-instruction-classrooms

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.