By Jon Freach, Lecturer in the Center for Integrated Design

This past semester, in UT’s first Introduction to Design Thinking course, students from across the university learned the principles of design thinking and applied them to real-world problems while working in project teams. Beginning with campus life topics such as health and wellness, meals, studying, and socializing, each team learned how to frame problems related to their chosen topic, learn about people and their behaviors, and apply those insights to improve products and services through concept prototyping and storytelling.

Students Meet “Design”

Practicing designers add great value by bringing our daily experience into the classroom. I had the privilege of teaching this course with two former colleagues who worked with me at frog design. They both have deep design research and interaction design experience: Katie Inglis and Alexis Puchek. They added continuity, perspective, and craft to every topic. So how did we actually teach design to such a wide variety of students, many of whom were unfamiliar with the subject? By using a slow and Socratic introduction through discussion of everyday objects, history, current events, and trending methods. Each class followed a sequence of discourse, lecture, activity, and share-out that enabled students to form conceptual models of design and build practice skills.

Learning a New Language

Design has a unique language that consists of Mental Models, Experience Principles, Ecosystems, Journey Maps, and Service Blueprints, all of which take a verbal and visual form. Our students needed to learn design definitions that factor into design methods. To demonstrate the need to learn a design language, we gave students a “pop quiz” in the first class: reinvent an everyday hygienic product such as a toothbrush. Lacking design literacy, they struggled to make confident decisions, were inhibited about visualizing their ideas, and slightly reticent to share their concepts at the end of the exercise. But they learned what it feels like to just make things up, a lesson that would prove more meaningful as they developed proficiency with formal design tools. The methods of design thinking enable practitioners to develop a human-centered mindset using toolkits that explore the boundaries of problems, discover meaningful insights, and translate research into concepts. Our class used frog’s Design Research Toolkit to learn this new language and apply a broad methodology to tackle common problems in campus life. As students “framed” problems, hypotheses about users emerged. When they interviewed fellow students and teachers about their experiences, they developed empathy. While discovering patterns within their interview notes, they formed insights and design ideas. By following a repeatable process and using formal design thinking tools, they built proficiency and gained confidence.

Working Together

Collaboration is a core principle of design thinking. Problems are complex, or worse, wicked. Even the most experienced, multifaceted designer will struggle to solve a contemporary design problem by herself. We grouped the class into four teams of 5-6 students each, making sure that each consisted of varying levels, majors, and genders. Their first objective was to get to know each other and begin the process of building trust and rapport. Their first lesson was about the value of dialogue in the design process; when they could talk about the nubby issues of their topic, they found they could arrive at a better definition of the problem. The act of voicing individual points of view enabled them to synthesize a stronger collective position and march forward with confidence.

Managing Time

In design practice, time is one of the most constant and effective constraints. Each group learned about the importance of managing and maximizing their time together, in and out of class, in order to accomplish the logistical tasks associated with planning and executing the challenging logistics of design research and design thinking. When groups couldn’t meet for a work session, it showed. If individuals didn’t complete a task, there was a ripple effect. The students learned the importance of choreographing their efforts in order to realize tangible outputs. Design thinking must lead to making, but this can only happen if teams are able to build a foundation of human insight in a timely, organized manner.

Understanding People

Ethnography, the act of finding, meeting, and interviewing people in order to understand what makes them tick is a deeply nuanced method of design thinking. Most of us don’t venture out into the world on a daily basis intent on engaging strangers in intimate conversations about personal topics. Yet, students had to learn the value of walking a mile in someone else’s shoes through first-hand accounts of their experiences. After choosing their field research methods, defining objectives, and writing research questions, each group split into two separate teams to venture out on campus and talk with fellow students about their healthcare habits, eating routines, studying techniques, and friendships. Interview teams consisting of a moderator and notetaker worked through the fear of approaching people for rapid “intercept” interviews; planned the tricky logistics of contextual inquiries held in dorm rooms, apartments, coffee shops, and study halls; and, facilitated participatory design sessions in order to learn about their experiences over time. Each team gained confidence as they interviewed more and more people, while gathering increasingly useful data to inform their concept design. Many experienced rejection in their attempts. All reported seeing the world through fresh eyes thanks to their newly found powers of observation.

Making Sense

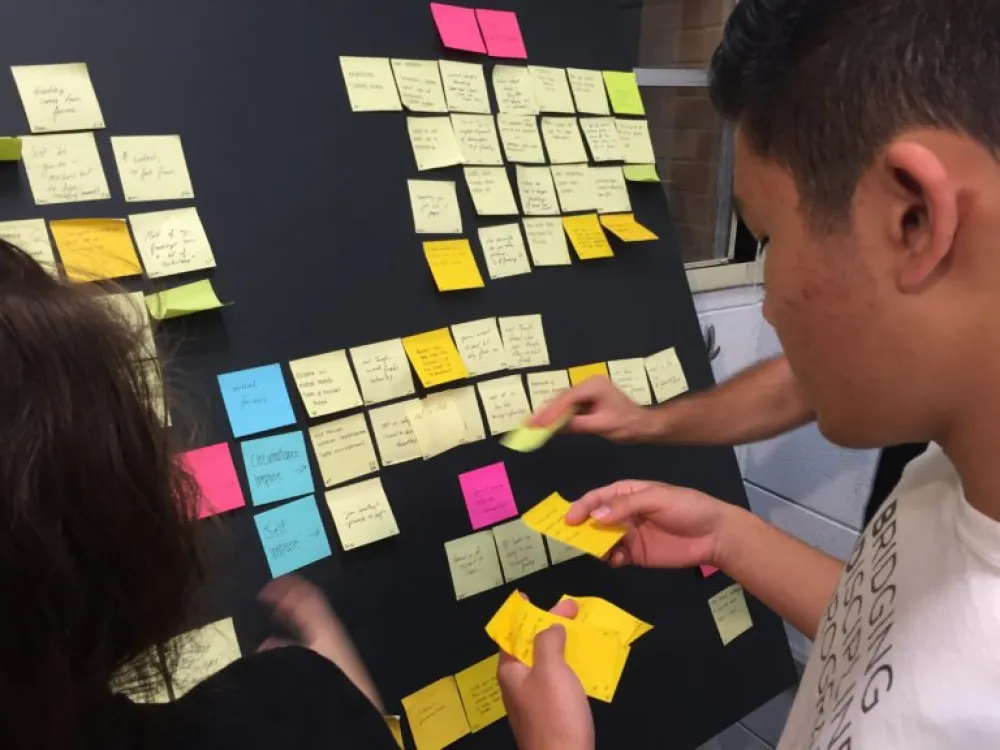

After gathering their data from interviews, the students regrouped and learned how to approach the process of sensemaking by finding meaningful patterns in their observations. Cutting through ambiguity is a content challenge in design, and the act of connecting dots between disparate and highly subjective data can push even the most seasoned professional to the brink of self-doubt. For a first-time design student, it can be inhibiting. Teams learned how to begin by cutting hundreds of observations down to sizable chunks. Teamwork took on new importance as individuals followed their natural impulse to simply discuss their observations, question their meaning, and form judgments by combining research observations with their own life experiences, and in the process learn how to handle their own biases through the act of design. All teams shared moments of doubt often coupled with sparks of insight, the kind of mood swing that is common throughout the stages of design.

Reflection, Visualization/Externalization, and Storytelling

Translating research insights into design ideas requires iterative cycles of reflection, dialogue, visualization, and critique. Students learned the value of sharing concepts informed by their research with each other and the participants they interviewed. Presenting their work during the beginning and ending of lab work sessions enabled them to act out ideas in the raw and get feedback from peers, myself, Katie, and Alexis. We wanted to know how their concepts fulfilled needs and traced back to research insights. This rhythm enabled the student teams to gradually build the story of their design work. Final presentations included an audience of peers, instructors, leadership from UT’s Center for Integrated Design, and design professionals who questioned students about the intent, methodology, core findings, feasibility, and value of their design ideas. By producing and delivering their final presentations, each student group learned about the interconnectedness of design thinking methods, and the systemic value (and challenges) of human-centered insight in the service of design.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, future classes may benefit from the increasing number of design thinking toolkits and methodologies emerging in practice. Within these alternate methods, students may also spend more time on certain techniques such as problem framing, planning and conducting ethnographic research, facilitating participatory design research sessions, or experimenting with technology to gather behavioral or environmental data over longer periods of time.

Design thinking must evolve in order to respond to changing industries, economies, and human experience. Likewise, our educational approach should consider these shifts in practice so that students can learn contemporary design skills, build the interpersonal qualities necessary to work and contribute to their chosen professions in designerly ways, and make their own mark on design futures which promise to be increasingly multidimensional and multidisciplinary.