By Michael Baker, MFA

How should educators teach game design principles? The short answer is to teach the principles of play—specifically, play as a mechanism for exploring interactive systems and a means for designing game levels.

Learning the principles of design is a crucial first step for any first-year student enrolled in a college design program. Compared to other forms of creation like fine arts, design tends to be more directly connected with industry and practice. Accordingly, design principles are generally grounded in processes “that work,” rather than theoretical constructs. This is not to say that design theory has no place, but new students tend to benefit from techniques that produce predictable outcomes.

Game design is no different, though a survey of intro courses and books on the subject might suggest otherwise. For decades, game design pedagogy and literature has promoted a “documents first—implementation second” approach where ideas are documented first and then implemented by a production team. While this process can work for veteran designers working within well-defined game genres, it does not, in my experience, work well for beginners. In fact, it often doesn’t work for experienced designers, as evidenced by the myriad corpses of big-budget games that have been littering the retail landscape since the 1980s.

How, then, should educators teach game design principles? The short answer is to teach the principles of play—specifically, play as a mechanism for exploring interactive systems and a means for designing game levels. While some simply refer to this as prototyping, I prefer the process described by Jonathan Blow as “Explorational Design.” This technique can be viewed as a “bottom-up” approach to designing play systems in that it requires designers to develop their “listening” skills to discover the latent play possibilities within a system. This is contrasted with the aforementioned more traditional “top-down” approach of “documents first—implementation second,” which subverts all development in service of a design document.

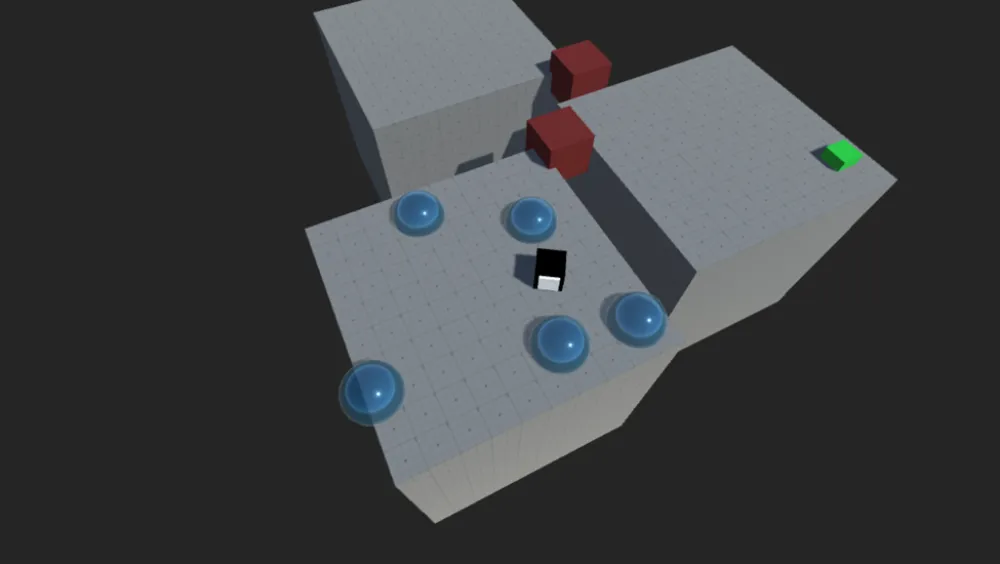

An example from the classroom is to provide students with a starting project that contains a simple, abstract, playable system. Within the first few minutes of play, students intuitively begin to invent challenges for themselves and start testing the limits of the system. This cycle of play- discover-challenge is the essence of Explorational Design. Students are directed to create structured challenges based on the interesting properties they have discovered. These challenges are then attempted by other classmates. Experienced game and level designers will recognize this as the design-playtest loop—the de facto method used across much of the industry.

Design is a practice with which most students at this level are unfamiliar, and in their first few attempts, they might superimpose elements of games they know as a way to make sense of the experience. This impulse to project external gameplay ideas is a natural one as many students feel strongly about the games they love. However, it’s critical at this early stage to underscore the importance of working within constraints.

After a few assignments like this, students are ready to begin integrating themed content. For this phase, I challenge them to identify themes suggested by the play systems—to seek themes that reflect and reinforce the discovered play around which they have designed challenges. Again, some will project ideas from external sources, and again, it’s crucial to guide them through this process to ensure they are “listening” to the systems.

When executed well, this development sequence yields a series of themed playable levels that feel “fun” to play, or in more abstract terms, create compelling engagement. Explorational Design is grounded in the act of play and offers a structured process through which students of foundations design can begin building their understanding of the interaction loop. It teaches them that great variety and richness can come from simple origins, that design opportunities can be discovered through play and that gameplay can be created through direct experiential means. For many students, this foundation demystifies design and provides a stable foundation for more advanced topics such as level design and design documents.

I have been teaching game design foundations this way for nearly 10 years, and in every case, students uncover play and design opportunities that I did not expect. This illustrates both a limitation of human ability and the power of this method. As a species, we are daydreamers and storytellers. Our brains are well adapted to cause-and-effect patterns, and accordingly, we can imagine and follow linear sequences as told through a narrative on the stage, page or screen. Unfortunately, human brains are not well suited to thinking through thousands or millions of unique interactive play sequences that occur in video games. However, we can overcome these limitations by practicing design through exploration and discovery. With some coaching and practice, students can learn to express the intrinsic qualities of interactive systems through play, which ultimately translates into engagement or “fun” for other players.

Michael Baker is a game developer and an Assistant Professor of Practice and Director of UT Game Design in the School of Design and Creative Technologies at The University of Texas at Austin.

Read more from the Journal of Design and Creative Technologies