By the Design Nine: Virginia Waldrop, Katherine Spitz, Taylor Smyth, Dainon Miles, Woody Green, Rachel Fresques, Jacquelyn Callahan, Anatoli Berezovsky, and Francisco Barrios

Introduction

In medicine, the patient history is key to solving the medical mysteries that doctors encounter on a daily basis. As a result, the medical interview is a highly valued, carefully practiced art. Yet the “history of present illness” as it is taught to medical students has several fundamental limitations. Medical interviews are constrained by a strict agenda, the interviewer is the expert, and connecting with patients is often praised but rarely required. One consequence of the traditional approach to medical interviews is that physicians often fail to discover the latent needs of their patients and may not even realize what they’re missing.

As part of the mission to rethink healthcare, Dell Medical School and the Design Institute for Health established the Distinction Track in Health Design and Innovation for third-year medical students. This year-long experience provides Dell Med students the opportunity to learn the process of human-centered design and equips them with the skills to catalyze change in healthcare. Using a design-led mindset, students learn to identify pain points in the current healthcare system and develop innovative solutions based around the needs of the people experiencing them. In spring 2019, nine medical students completed the first iteration of the Design Distinction at Dell Medical School. Reflecting on this experience, we were surprised by our ability to cultivate deeper connections through human-centered design compared to traditional clinical interactions. In this article we will compare the qualitative interview as practiced in both medicine and design. Through discussion of both approaches, we will explore how the medical community can use the principles of human-centered design to deliver care that better responds to the needs, behaviors, and values of their patients.

Medical Interviews

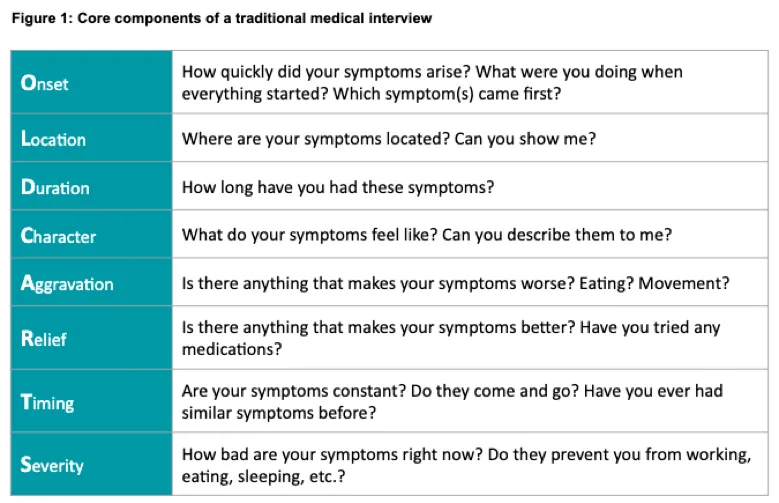

The fundamental purpose of a medical interview is to gather information about a patient’s illness to identify potential causes for their symptoms and direct subsequent care. The structure of the interview is formulaic, enabling the physician to gather actionable information in a consistent, organized, and time-efficient way. The traditional “OLDCARTS” interview (figure 1) is taught almost reverentially to thousands of medical students across the country.

During clinical rotations, medical students are expected to gather the same information for each patient and report these findings to their supervisors. There is often little time to collect information about a patient that is not included in the traditional interview format. Additionally, a student’s proficiency with the interview process is a major component of their clinical evaluation.

The medical interview has evolved this way to facilitate the delivery of safe, efficient care in a dynamic clinical environment. By streamlining the interview, physicians can gather a large amount of data in a short amount of time. The use of a standard interview format also maximizes the efficiency of the data-sharing phase, when patient information is communicated to other members of the healthcare team. Finally, the traditional interview format ensures patient safety in a teaching environment by enabling students to gather clinically valuable information, even though they may lack the expertise to act on it.

Despite its benefits, the medical interview has significant shortcomings which often limit the depth and quality of information elicited during a patient interaction. The standard interview affords little space for improvisation. The patient history frequently becomes a long list of blanks that are filled in by the patient, which eliminates opportunities to discover unexpected or surprising insights. Furthermore, the interview is typically led by the physician—not the patient. This practice is based on the implicit assumption that the physician knows what questions are most pertinent to each patient’s care.

With the physician positioned as the expert, the patient loses the agency to discuss what is most important to them. They must adopt the role of non-expert when it comes to their own body and health. This dynamic exacerbates the existing power differential between the physician and patient, with the physician eliciting information and the patient providing answers with the hope that subsequent medical recommendations will be in their best interest. Perhaps the most glaring shortcoming, however, is the paucity of questions about a patient’s experience beyond their physical health. While some questions in the social history can provide insight into the patient’s life, motivations, and concerns, these are inevitably the first questions to be cut if there are any time constraints (and in medicine there almost always are).

Design Research

On the surface, the traditional medical interview shares many similarities with the type of qualitative interview that forms the bedrock of the design process. In both scenarios, the interviewer asks a series of questions about a subject’s past and present state to uncover information that could manifest a novel future state. In medicine, the physician gathers information about a patient’s symptoms and medical history. This information is combined with objective data to reach a diagnosis and develop an effective treatment plan. In design, the designer gathers information about the current experience of a potential end user to identify unmet needs and create a solution to better meet those needs in the future.

To create something impactful, designers have to understand who their users are and how they interact with the world around them. While creativity fuels the generation of new ideas, a designer’s empathy ultimately provides the foundation for effective person-centered design. For this reason, good design starts with good research—a systematic attempt to empathize with potential end users by learning about their needs, values, and behaviors. Design research requires careful listening and observation of everything that is being communicated by the interviewee.

Despite their superficial commonalities, the types of interviews employed in design and medicine differ in several fundamental ways. In design, the interviewee is the expert, and the designer must establish this expectation at the start of the interview to maximize the quality of information gathered during the conversation. The role of the interviewer is to provide a platform for the user to communicate their thoughts and emotions. As a result, design interviews tend to be longer and less structured, providing the flexibility to explore unexpected findings as they emerge.

Unlike physicians, who are trained to fit incoming data into recognizable diagnostic patterns and clinical algorithms, designers make it a point to acknowledge and challenge their preconceptions. To this end, design researchers ask open-ended questions, listen closely, and repeatedly ask “why?” to uncover latent motivations underlying the behaviors or emotional reactions that define a person’s experience. This process creates opportunities to uncover surprising insights that may not surface in structured interviews organized around a strict agenda. While designers employ divergent thinking to discover novel insights, physicians use convergent thinking to discover the pre-made mold within which their interviewee fits.

Nevertheless, the design interview poses its own set of challenges. These interviews are time-consuming and frequently generate a large amount of disparate information, which the design team must then sort through retroactively. Given the depth and complexity of a design interview, it is virtually impossible to extract strong and meaningful insights in real time. Thus, the design team must collaboratively download the interview as soon as possible to minimize the deterioration of data over time and engage in a lengthy process of synthesis to identify key patterns and conceptual relationships across many interviews. Finally, design interviews require a leap of faith on the part of the interviewer—a belief that with enough digging, the interview will uncover content that will lead to the creation of rich insights, which will provide the seeds for valuable solution concepts.

Integrating Elements of Human-Centered Design into Traditional Medical Interviews

Admittedly, the nine of us are relatively new to both medical interviewing and human-centered design. As we advance in our careers and become less concerned about our ability to assign the correct diagnosis, we may find that traditional medical interviewing lends itself to a great deal of creativity and empathy generation with our patients. With more knowledge and experience, we will gain additional tools to collaborate with our patients to design treatment plans that truly meet their needs. We also acknowledge that many physicians will never be able to create time in their practice for the in-depth interviewing and synthesis required by true design research. Despite these considerations, it is clear to us that medicine can incorporate elements of design to improve patient outcomes. We challenge the medical community to ask the following question: How might we start every medical interview, first and foremost, with empathy?

In many ways, the “history of present illness” and “subjective” portions of the medical interview already lend themselves to a design-led approach. As medical students, we are taught to elicit information from a patient about their illness in their own words—and to document these findings as direct quotations in the chart. There are some simple ways in which this portion of the interview could be tweaked to incorporate elements of design research. Physicians could start the interview by reminding the patient that they are the expert when it comes to their symptoms and experiences, reinforcing the patient’s expertise in their own body and life. Going even further, physicians could consider the following provocation: how might we make the medical interview feel like a contextual interview in the patient’s home, regardless of where it takes place?

Importantly, highlighting the expertise of the patient does not necessitate minimizing the expertise of the physician. Patients seek out physicians because they have deep expertise. Not only do physicians help elicit information from the patient through careful questioning, they also integrate it with a vast amount of additional data to make recommendations about the best path forward. Nevertheless, the patient’s personal expertise about their body, mind, and life often goes unacknowledged in clinical practice. In some situations, clinicians will describe their patients as “poor historians”—but who are we to judge how they tell their own stories?

Setting expectations before the interview will be key to reframing the traditional interview format.

The subjective portion of the interview will lay the foundation for open-ended data gathering and help the physician incorporate another key element of design interviewing—asking “why” more often. “Why” questions often give rise to the most valuable insights during an interview. Physicians should establish an expectation that they will be asking “why” throughout the interview—not out of skepticism, but to better understand the patient experience.

Conclusion

Beyond any one recommendation, we challenge physicians to set aside their preconceptions and ingrained habits to rethink the medical interview. To address the numerous issues in our healthcare system, we must allow room for innovation and embrace creativity in all aspects of our practice—even in one of its most sacred skills. Let’s prototype an alternative to the “OLDCARTS” format, collect anonymized quotations to share with colleagues during a synthesis session to extract insights about the patient experience, and stop interviewing “patients” and start interviewing “people.”

In design, we say that no interview guide survives the first interview. Why should medicine be any different?

The Design Nine are the first cohort of Dell Medical School students to complete the Distinction Track in Health Design and Innovation.