By Harsha Kutare and Somnath Chakravorti

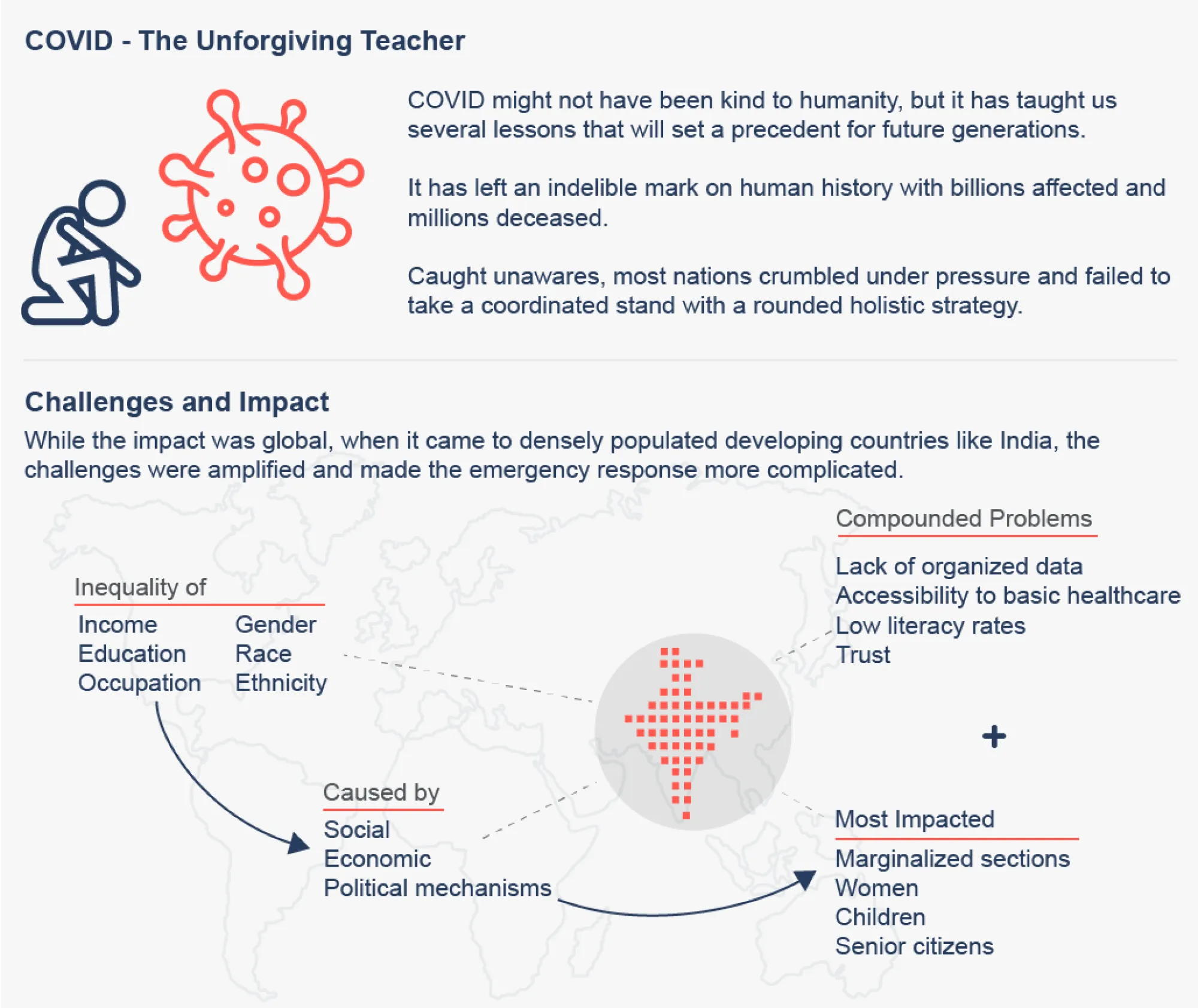

While countries continue fighting against COVID-19, governments and citizens are forced to ponder what went wrong, where were the gaps, and what reforms should be made so that humanity is better prepared for such “wicked” problems in the future.

One of the major hurdles was data and information inadequacy, which makes it imperative to design a citizen-centric, data-informed, sustainable digital governance model. More and more governments are moving towards treating their cities as products and citizens as the consumers.

Data & Information Inadequacy

Data and information inadequacy hampered the response put forth by the Indian government, police, civic bodies, healthcare institutions and community support groups against the pandemic. The gaps manifested themselves in several ways.

Delayed and inaccurate threat assessment

It took India three months after its first COVID-19 case and two months after World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic to act upon [12]. With the right sense of urgency this precious time could have been used to prepare medical facilities and put quarantine measures into place.

Rapid dissemination of disinformation

Though around 22 percent of Indians live below the poverty line [1], around 60 percent of Indians are expected to have access to a smartphone [2] by 2022 with around 30 percent of the total Indian population using social media platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook [3]. People rely on social media for news and information. However, these social media platforms were rife with fake news, untested remedies, fear mongering, communal hatred and inaccurate emergency response contacts.

By the time the government came up with the official communication channels of "Aarogya-setu," "Appmithra," Official Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) and broadcast of emergency numbers via telecom providers, the damage had already been done.

Inefficient track & trace to contain the spread

In India, a huge section of society migrates to cities from villages for sustenance. They work odd jobs and stay in shared accommodations without rental agreements, making it difficult to identify and trace them [9]. The first impact of the pandemic was on odd jobs in construction, restaurants, household help, security and housekeeping in building societies, which led to:

- Loss of livelihood

- No financial aid—largely unbanked population

- High rental costs in big cities

- Disappearing street food stalls/ vegetable markets

With the above challenges looming, the migrant population wanted to move back to their villages. However, in the absence of proper data, the government was unable to even assess the volume of migrants trying to move between states, which led to huge gatherings at bus depots and train stations.

Knee-jerk reactions of the masses

There were mixed responses from the general public. It started off as an attitude of indifference with several news channels claiming that the hot Indian climate was not conducive to the virus. With WHO being unclear on classification and nature of the threat, the situation converting into a pandemic seemed a distant possibility.

However, with increasing cases, the absence of a vaccine, high prices for testing and limited hospital beds, panic quickly gripped everyone, irrespective of their socio-economic backgrounds.

Some sections of society, however, still disregarded the norms of social distancing, use of masks and sanitizers and avoidance of public gatherings [10]. This added fuel to the already spreading wildfire of positive cases.

Lack of data for pointed recovery interventions

Financial aid to the lower income groups

The government of India introduced several schemes including financial aid to migrant workers, farmers and the economically challenged strata of the society [4] during COVID. India stands second in terms of the unbanked population [5] and even Jan Dhan–Aadhaar–Mobile (JAM) trinity programs have been unsuccessful in increasing inclusion. Hence, financial aid could not reach the most needy populations.

Supply of basic necessities

The government had declared its intent to distribute basic food items. But without the data around location of distribution centers and the volume of people expected, the predictability for quantity couldn’t be assessed accurately. People had to return empty-handed after a day’s wait as rations vanished at these food distribution centers with never-ending queues [6].

Healthcare & medical inadequacy

The national number of hospital beds per 1,000 residents in India is around 0.55 [7], and the number of patients per doctor varies from 2,000 to 44,000 [8]. Data is crucial to locate, distribute and divert the medical fraternity to the most affected locations. Lack of critical patients-to-doctors data, a huge socioeconomic divide, and a lack of critical medical facilities made it immensely difficult to provide an effective response.

Lack of support for the most vulnerable populations

The elderly population (aged 60 and above) is especially vulnerable, given existing medical conditions. The availability of hospital beds for the elderly population in India is 5.18 beds per 1,000 people [7], which is extremely insufficient. Also, stratification data on the elderly, children younger than 10, pregnant women, and patients with existing medical conditions is only available in fragments in government chronicles and hospital records which makes it difficult to reach out to these vulnerable populations in times of emergency.

Citizen-Centric Digital Cities

Design methodology can be used to discover and define these problems. It will help in analyzing who is impacted and what factors contribute to the problems.

Services that are most desirable, viable and feasible can be designed. Once deployed, services can be monitored, evaluated and pivoted for sustainable development.

The three components of designing these “Citizen-Centric Cities” are citizens, government, and technology. Designers equipped with design thinking tools and a user-centric design approach can help improve the lives of the citizens and fight any future wicked problems.

Citizens

It is very important to identify key citizen segments with a conscious attempt to move towards inclusive systems by bringing marginalized/ underprivileged citizens from both urban and rural areas to the core of digital governance initiatives.

Mapping of citizens based on geolocations/UID [11] and documenting their movement is essential to having a universal health record system. It is crucial to understand their socioeconomic conditions along with their challenges, desires and aspirations.

Government

The relationship that citizens have with governments is evolving worldwide into an inclusive approach from a culture of enforcement. India is testing and evolving to reach an optimum design with customers at its center.

Ministries are exploring public-private partnerships with rapid feedback from citizens to create integrated datasets and data-informed, self-enforced and sustainable community policies. By taking a citizen-centric approach, leaders can better understand the needs of citizens and translate them into targeted, effective service-delivery improvements and seek public contribution for maintenance and uplift of services.

Technology

Technology builds a bridge between the needs of citizens and policies created by the government. It also assists in smooth implementation of initiatives and policies, and tracking progress in key parameters.

By collecting non-intrusive, non-identifiable data, including public health records, and converting them into actionable insights, government can build cities that are predictive, responsive, efficient, and self-sustaining with viable emergency responses for any calamities while maintaining trust.

Technology played a key role during the pandemic, and successful responses used it to enable the design of effective systems to fight back.

Intersections of any Two of the Primary Pillars

Digital inclusion (citizens & technology)

Technology can help capture the implicit requirements of citizens and create cities that cater to them. It can also help us understand the stratification of the citizen base, their origins (especially for migrant populations), occupations, financial stature, dependents, and health, family and education requirements.

Technology provides benefits via linkages of Social Security numbers, bank accounts, tax records, etc. A city dashboard can be used to drill down to the lowest impactable metrics: e.g. doctor-to-patient ratios, number of parishioners per church, peak traffic to metro services, road widths by resident population, etc.

Digital governance (government & technology)

The aim of any government is trifold: create the right policies, execute them to benefit the targeted audience, and monitor performance to re-pivot. Technology plays a crucial role in:

- Creating policies based on analysis of data collected on usage of city resources, social media ramblings, corporate interactions, street chatter and formal feedback mechanisms.

- Ensuring benefits reach the expected recipients (financial aid via UID [11] and bank account linkage), adherence to policies (tax regimes, traffic regulations, health benefits) and grievance redress.

- Measuring effectiveness of policies by providing early feedback, scheme-wise accounting, impact assessments, solicited feedback, etc.

Policies for sustainable development (government & citizen)

Communities defining local regulations need no enforcement, primarily because the regulations come from the members. Similarly, policies defined with citizen involvement would be self-motivated.

Civic bodies should define policies applicable to all strata of citizens, including any migrant populations. For example, a primarily migrant population would look for favorable labor policies, a trading populace for trade incentives, a farming community for favorable agricultural loans and commodity markets.

Outcome: The Citizen-Centric Digital City

As discussed above, change can be brought at the intersection of any two components of citizens, government and technology through digital inclusion, digital governance and policy reforms. However, true sustainable development can be achieved only by the right convergence of all three. To achieve this, a huge social change is necessary, which is where designers play a crucial role.

With the user-centered design and systems thinking approach informed by the power of data, designers could help in understanding connectedness and interplay of the systems and citizens. This understanding will lead to transformative social changes.

A city command center dashboard will provide decision makers with a powerful real-time tool to assess the overall condition of the city with alerts/notifications whenever any predefined parameter breaches limits or shows unusual behavior. Drilldown is possible to country, state, and even block levels, with further navigation to the specific “metric” that has faltered.

City Command Center – Sample Tracker for COVID

Read more from the Journal of Design and Creative Technologies

References

[1] The Financial Express, September 21, 2019

[2] The Economic Times, July 09, 2020

[3] Livemint, February 12, 2020

[10] Deccan Herald, March 29, 2020

[11] UID – Unique Identification provided by UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India)