By Gray Garmon and Katie Krummeck

In the fall of 2019, the Aga Khan Foundation (AKF), an international development organization and agency of the Aga Khan Development Network, asked us to co-create a design-based innovation process for public schools around the world. Specifically, these schools were participants in the Schools2030 initiative—a globally informed, locally rooted 10-year learning improvement program working with 1,000 pioneering preschools, primary schools, and secondary schools across 10 countries on four continents.

This initiative is funded by a coalition of nine private education philanthropic partners to support teachers, school leaders and students to develop and design solutions that promote holistic, quality learning for all. This effort is inspired by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals set to be reached by 2030.

While the initiative and the scale of potential impact were exciting to us as designers, the real question for us was: how do we co-create a set of tools that can help produce meaningful design work led by those closest to the challenges they were facing? This article tells the story of the development and deployment of these resources, as well as the early signs that they are making a difference.

We are excited to share the story of this work thus far for several reasons. Firstly, as design educators with over ten years of experience training and coaching people to take up design as a new way of working, we were thrilled to be able to apply the knowledge we have gained to help set up this initiative for success.

Secondly, the scale and potential impact of Schools2030, while daunting, is deeply motivating and inspiring. If we can support 1,000 schools in such diverse places as Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Portugal, and Brazil to do meaningful design work that leads to better outcomes for children, then we believe we have a model that could make an even bigger impact over time.

Most importantly, we have developed a strong set of values and beliefs that inform our work every day, and which resonated especially strongly on this project. We believe that educators are designers. Every day, teachers create experiences for their students through developing student goals, considering different student needs, iterating between lessons, and impacting student learning outcomes. We believe that empowering educators with foundational design tools and methods will not only amplify the work they currently do, but it will also amplify the learning potential of their students.

As our work began in the fall of 2019, we started with the goal that any teacher in the world could pick up the Schools2030 Human-Centered Design Educators Toolkit and go through it, page by page, to complete a locally-driven design process with fidelity. They can use it to create human-centered projects that will improve the holistic learning outcomes of their students. This was a collaborative process, and Munir Ahmad, AKF’s Global Innovation lead, shared his perspective on why the Foundation chose to focus on design as their tool for change:

Today, the global development and education landscape is facing unprecedented change. During the last months we have all seen the largest disruption of education systems in history due to COVID-19. In this context, social innovation holds the promise to offer a new framework and mindset to help the education community (students, teachers, parents and others) to collaboratively create more impactful and affordable solutions to solve some of the most pressing problems in their communities and schools. Design methodologies such as human-centered design offer a structured process that can help navigate this complexity, and create the necessary creative confidence to enable all actors to become active change agents. For AKF it is critical that we invest in nurturing a community of creative problem-solvers equipped with design and innovation competencies in order to sustainably improve the lives of people living in poverty.

As we dug into this complex project, we established our work on three main pillars: Design Principles that would guide the development of the project in a human-centered way, Design Tools that would enable educators to practice design thinking, and Design Training that would build capacity in local teams to guide the work of the school teams.

Design Principles

In order to develop the design principles that would steer our work during this project, we interviewed educational leaders from each country. These conversations provided context that informed the creation of the toolkit and the training sessions in a human-centered and user-friendly way, while also staying accountable to our stakeholders and clients.

The Design package must…

- Support a design process that is driven by those on the ground, with the goal that they will build evidence and conviction toward solutions that will create holistic quality learning for all

- Support a design process that generates solutions that make sense in the educators’ context

- Support a design process that is grounded in data gathered through the offline app Promise and/or the aspirations of the school leader and educators

- Support stakeholders to identify challenges and solve them using a human-centered approach

- Support school leaders and teachers to design solutions that are best for their context while also “not starting from a blank slate” by drawing inspiration from learning and best practices

- Communicate an understanding that “choice” is a key element of local work; educators are not “told” what to do in their communities

- Be broad enough that it is applicable across a wide variety of contexts

- Not have hard-to-translate jargon

- Provide a simple enough process that it can be completed with minimal coaching and time investment

- Include train-the-trainer supports with a “trickle-down” structure of capacity and expertise

- Include appropriate design research techniques for preschoolers as well as students in primary and secondary schools

- Support a process that eliminates power structures in the work

- Support building local capacity so AKF is needed less over time

- Assume participants will be working in teams while also creating tools that can be used independently

Once we developed these design principles, we were able to share them with the team at AKF to get feedback and refine them. After the process of refining these principles, we continuously returned to the principles as our northstar for the project.

Design Tools

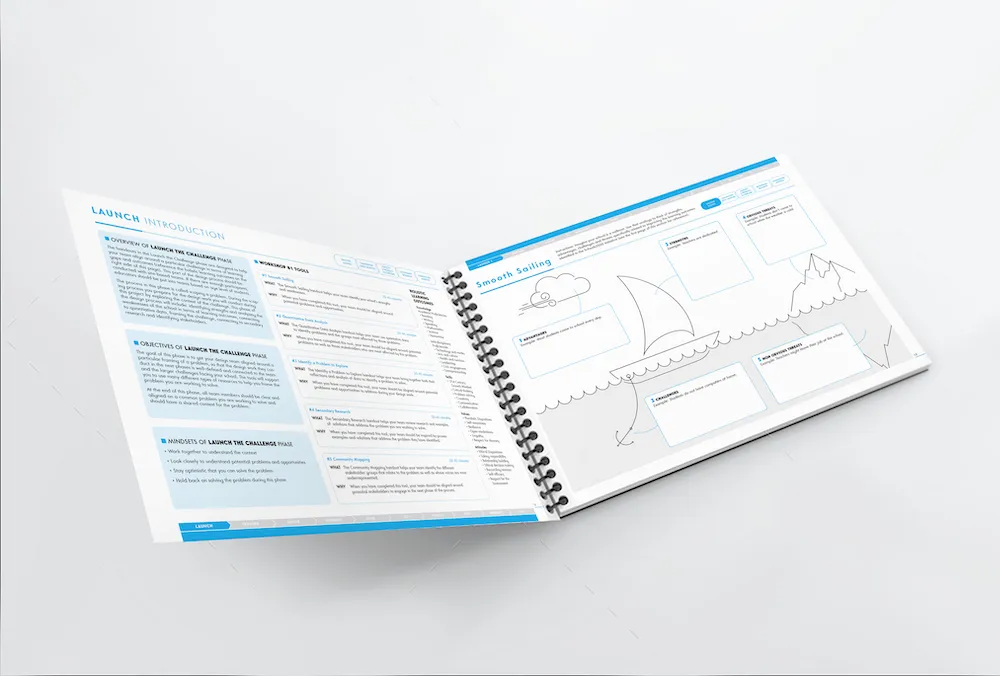

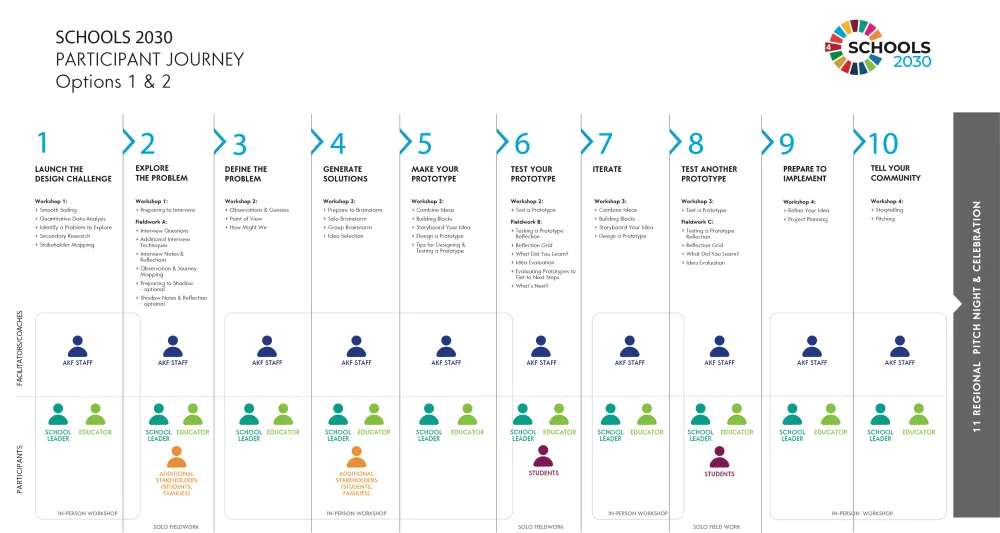

We created a collection of resources for educators, school leaders, and facilitators. The main resource is the Schools2030 Human-Centered Design Educator Toolkit. This 184-page workbook outlines a ten-phase process. Teams of educators in local schools use the toolkit to identify, research, and prototype solutions that will lead to improved holistic learning outcomes for their students. The toolkit is supported by facilitators from the AKF and regional Schools2030 partners. Every phase of the design process is a cycle that can be completed at a self-directed pace and redone as many times as needed until the team is ready to move to the next phase.

Our goal was to create a tool that could be adapted to many different contexts of culture, language, school, and team. We researched many other toolkits, method cards, websites, and videos aimed at providing introductory resources for human-centered design, but in the end we felt that none had the necessary explanation and support needed to empower someone to navigate an otherwise ambiguous and open-ended process.

We leveraged our experience as both designers and educators to scaffold the toolkit using the best practices of adult learning. We edited repeatedly for clarity, accessible language, and user experience.

The Schools2030 Human-Centered Design Toolkit.

Design Training

The final pillar of this work was the training of Design Trainers. We started in Nairobi, Kenya in early 2020 with AKF’s Schools2030 staff and partners from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania and a team from the Regional Education Learning Initiative (RELI), a network of more than 80 civil society organizations throughout East Africa dedicated to improving the quality of learning for all across 26,000 schools.

Halima Shaaban, the Schools2030 National Coordinator in Kenya, participated in the in-person training in Nairobi. For her, “The best part [of the training] was having an opportunity to experience the human-centered design journey with my program team [as well as] seeing the culmination of the work we had put into refining the journey and toolkit.”

Halima also shared that her most important new insight was “the realization that the process should focus on awakening the teachers’ (already existing) design instinct, and to avoid presenting it to teachers as a new concept, because they already experience design in their everyday classroom.”

Halima sees the very high potential of the toolkit for empowering teachers as design thinkers in the classroom:

The toolkit is a comprehensive guide for the teachers on navigating the human-centered design journey for their contexts. I especially like two things: 1) The format of the toolkit with the introduction, main tools and the transitions pages. The transition pages are of particular importance as they give teachers an opportunity to consolidate their thoughts and work [summary], discuss and agree as a team on the next steps [alignment], and finally have reflections on activities that were difficult and how they may support each other to work better as a team. The reflection page is also important for me as it gives me an idea of where teams are struggling and may need support. And 2) the mindsets outlined for each phase—through them, the teachers are made aware of the potential mental blocks they may face while designing and the tips [mindsets] to navigate these blocks.

The work is now spreading. Halima and a team of colleagues recently started training new teams in the design process while leveraging the Schools2030 Toolkit. For her, the best parts of that process have been “having the teams see the process as a journey and making the links between the phases, having the teams discover the human-centered design process as a structure where each phase provides a foundation to build the next phase on.”

Throughout this journey, Halima has learned “the power of empathy. As a facilitator who has gone through the same journey, I am more understanding of the challenges and uncertainties the participants face and therefore am able to support them better (partly by sharing my own journey and struggles with them).”

Continuing the Training During the Global COVID-19 Pandemic

In the face of global shutdowns and school closings from COVID-19, we decided to pivot to an online training model. Over the summer of 2020, we hosted 13 online sessions using Zoom and Mural for all 10 countries in the Schools2030 initiative. Although at first we worried that it would be inferior to the original in-person training, it instead allowed us to build a more cohesive and diverse global design community of AKF leaders and educators who were learning and designing together across regions. We began to see that the struggle of parents in Kenya was similar to that of parents in Tajikistan. The team from India inspired us all with the creativity of their prototypes.

Each country had a design team that learned the human-centered design process by using the tools to solve a pressing challenge. Because of the complexity of different contexts across the globe, teams were able to choose between two design challenges: How might we support learning from home? Or, how might we reimagine school reopening in the times of COVID-19?

Each country developed unique ideas for improving holistic learning outcomes that met specific needs for their community. The idea that was developed in Kyrgyzstan focused on teaching student self-efficacy through hygiene and hand-washing.

The project idea from India focused on a physical box of learning resources that would be mailed to families in order to support hands-on learning. The contents of the boxes would be generated by partnering with local women’s self-help groups that were also making masks during COVID-19. By drawing on what the team learned from their design research, and taking inspiration from companies like KiwiCo in the US while also emphasizing the need to make their solution more affordable, locally relevant, and aligned with the local education curriculum, the team came up with a creative and sustainable solution. Arjun Sanyal, Senior Program Officer - Education and interim coordinator for Schools2030 at the AKF in India, shared his thoughts about the potential of the toolkit as well as his own learning experience during the online course.

According to Arjun, “The best part of the online workshops was being able to virtually get together with colleagues from other countries and listen to their ideas, experiences and challenges during COVID and their design journeys. Though we were at very different stages [of where the countries were in terms of COVID], it was great being part of this global community designing solutions for continuing learning against all odds.”

Arjun notes, “The potential of the toolkit, for me, is not in the solutions we bring out each year. The main learning from the toolkit is within the process itself, and all the skills one can acquire while going through the process. Understanding children and parents through empathy interviews, learning how to ask open-ended questions, continuous observation and reflection, active listening, collaborating with others, critiquing positively, taking failure in one’s stride—all are great learnings, and would benefit the area of teacher professional development. Even if that teacher’s designed solution does not work as we expect, at the end of the year, she/he will still be a better teacher.”

For Arjun, “The best part of the design work experience is that I got to be really hands-on, especially during prototyping and testing. In a situation where all work was moving online and we were glued to our screens, cutting cardboard boxes to make prototypes and engaging in something tactile helped me feel, helped me think differently. The best insight I gained from this process this time is that our ideas do not need to be complicated; keeping it simple works.”

For their team, he reflected, “A big challenge in implementing our solution about Learning at Home kits/Box of Bold Ideas is how do we make it really affordable? Can we make a home-based learning kit for less than $2 USD that can be distributed through the mail? This challenge in itself is really exciting as we have to treat each round of implementation as a learning for the next one. We have to be creative about how we make a box, what is in the box, who makes it, how it is delivered, etc. Each decision will save a few cents, but those few cents become critical. Great challenge to really push our creativity.”

This is a decade-long initiative, and 2020 is just the start. It was already an ambitious program, and it had to pivot once because of an unprecedented global pandemic. However, we were able to use the strength of design’s adaptability to create a toolkit aimed precisely at facing ambiguous challenges. This summer we’ve gotten a glimpse of the possibilities that could come from applying human-centered design to school-based challenges, letting grass-roots decision making guide the development and funding of solutions. More than half a million US dollars were distributed for the 10 ideas generated from the 13-week course—funding solutions that were previously not on the global radar of what should be done in response to the educational crisis of COVID. These seed grants came from the Schools2030 program and will provide critical roots for further evidence generation and locally driven innovations that have an impact on learning. We are hopeful that this new way of working will create solutions with better outcomes for students. We know for certain that the toolkit and trainings have already had a positive impact on local education leaders.

Dr. Andrew Cunningham, global lead of education at the AKF, reflects:

At the heart of the Schools2030 approach is a recognition that schools are the center of social change, not the target of change. Rarely are school leaders, teachers and students perceived as reservoirs of innovation, or invited to listen, reflect, and self-discover the wisdom that lies among them. Even rarer are instances where invitation, dialogue and self-discovery lead to community actions and external investments, guided by data that the school collects, processes, and uses to achieve holistic learning outcomes for all. The Schools2030 Human-Centered Design Toolkit provides the global education community with a profoundly unique and refreshing new opportunity for approaching education improvement through a more empathetic, inclusive, and empowering lens. Together with 5,000 educators, 50,000 students, and 1,000 school communities, Schools2030 is on track to now continue prototyping and iterating the Schools2030 Human-Centered Design Toolkit as it supports teachers, school leaders and communities to develop thousands of new, locally rooted innovations about how best we can support children’s equitable and quality learning for decades to come.

We know that there is not one single solution that will fit all schools and communities. A process like the one supported by the Schools2030 Human-Centered Design Educator Toolkit from the Aga Khan Foundation will be able to empower individuals close to the challenges facing their communities to create solutions that have a far greater impact.

This fall, as teams prepare to launch the Toolkit with their schools, Krummeck and Garmon are continuing to support the implementation of the process while also gathering and synthesizing feedback from participants this summer. A new iteration of the Toolkit will be shared on the Schools2030 website in the coming year.

To learn more about the Schools2030 initiative, please visit their website: https://www.schools2030.org/

Read more from the Journal of Design and Creative Technologies