By Cassidy C Browning

Introduction

Although I am relatively new to design thinking, each tenet I have encountered is as familiar to me as my own hands. To me, the fabric of these methodologies was clearly woven from feminist,i queer, Hip Hop, Jazz, and Indigenous pedagogy and performance. Queer of color and feminist performance spaces are where I feel possible—as I am, as I have been, and in any way that I could or would be. My work, research, classrooms, and service have been dedicated to these forms; design thinking felt like home, too.

I began my official journey with design thinking just one year ago, but my journey with human-centered practices has spanned my entire life. My formal design thinking experience comes from working in the School of Design and Creative Technologies’ Executive and Extended Education unit at the University of Texas at Austin, wherein I supported, prepared, delivered, facilitated, and generated design thinking workshops for more than 1,200 corporate, school district, and campus group participants.

Many of our workshop days end with the recording and sharing of “wow moments”: ideas and connections that viscerally struck you, surprised you, and which you wanted to remember. Last winter, a participant articulated the depth and potential of human-centered work: Design thinking gives you the ability to be free.

Project

Vanessa Newman, an inclusivity- and community-focused strategist and designer, made a crucial point during the Where are the Black Designers? conferenceii: “So many Black people are designers—every day, we have to design new solutions to navigate systemic racism. That, in and of itself, is design. Black people are naturally designers. Everything that we do, in a sense, is design.”

While sociologist and activist W.E.B. Du Bois identified “double consciousness”—that Black people living within white supremacist contexts are always already conscious of themselves through that framework in addition to their own—Newman identifies the effect of this multiplicity: Black people are always already designing their paths between these perceptions.

Intersectional, queer, and feminist analysis have adopted and expanded Du Bois’s understanding of the gaps between one’s identity and that which is prized, given power, etc. Newman’s point can also be extrapolated: we should intentionally look to women, queer people, and people of color as designers, as the facts of their being necessitate design.

Origin stories of design thinking commonly spotlight the work of a few white male writers, ironically fashioning a homogenous and linear creation story for a communal and iterative methodology. Multiple panelists featured in the Where are the Black Designers? conference, including Jasmine Burton, Antionette Carroll, Elaine Lopez, and Dori Tunstall, contradicted the cursory premise of the title, arguing that this is only a question because Black designers and Black design have been excluded. This article is a project of decolonization and of emancipatory and transformative researchiii, and my agenda is to shift power and recognize that design thinking and human-centered work have deep roots within marginalized communities.iv

Design thinking is a vital tool for the wicked problem of social justice, as its human-centered methodologies are also diversity-, equity-, and inclusion-centered. In order to maximize this potential, I locate expertise in, and take guidance from, feminist, queer, Indigenous, and Black work and individuals. The characteristics of white supremacy culture identified by Tema Okunv of Dismantling Racism (dRworks) reads like a list of everything design thinking aims to disrupt:

- Perfectionism, Only one right way, Either/or thinking, Defensiveness

- Sense of urgency; Quantity over quality; Progress is bigger, more

- Worship of the written word

- Individualism, I’m the only one, Paternalism, Power hoarding

- Fear of open conflict, Right to comfort

- Objectivity

Design thinking and human-centered methodologies inherently challenge white supremacy; this is why the adoption of these practices requires structural and cultural change within organizations.

As it is important to be transparent about my positionality: I move through the world as a white, middle class, cisgender female, and before this job, my career included theatre practice, scholarship, and teaching; the service industry; and administration, management, and human resources.

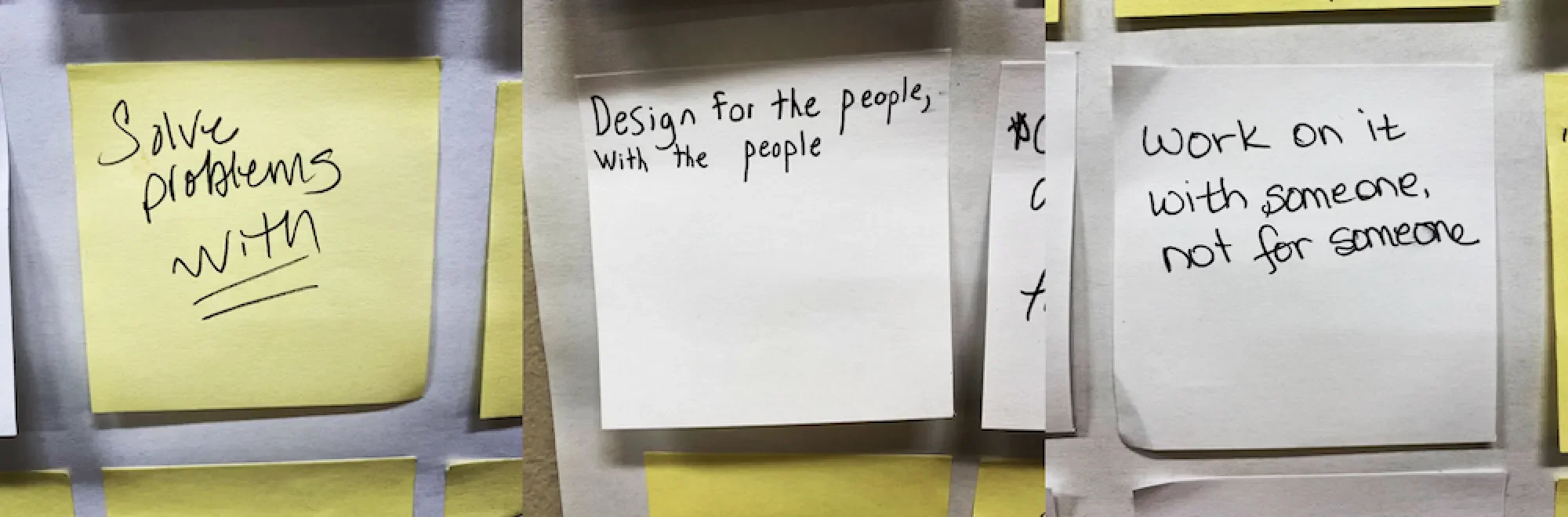

With > For

During the “Reimagining Public Safety: Justice, Equity, and Anti-Racism” roundtable, social justice organizer Keellee Coleman makes a powerful intervention: “I want you to be a co-conspirator—I don’t need an ally. I want you to be in the game with me.” At a time when there has been a huge amount of engagement with the term, “ally,” what constitutes an “ally,” who can bestow this term, etc., Coleman redesigns and reframes the conversation to eliminate hierarchies and invite action in the form of co-creation. Coleman’s move also situates all people within “the game,” which is more accurate, as systems of oppression oppress everyone. Antionette Carroll, an educator and leader in diversity, equity, and inclusion and design, advocates for “not just individual, but collective liberation”; collective liberation can only be achieved by working with, not for.

The central design thinking tenet of co-creation (the importance of collaboration, the power of collective intelligence) is the same methodology used by Sharon Bridgforth when she stages her performance/novels and conducts her audiences of “active witness-participants” in sound, song, words, and movement. It’s the same as the storyweaving used to craft layered theatrical pieces by the Kuna and Rappahannock sisters and elders of Spiderwoman Theater. It calls forth the ciphervi—or sacred circle—from Hip Hop Theatre, as much as it invokes the multiplicity, improvisation, and polyphony of the Theatrical Jazz Aestheticvii and the communal, devised tactics which generated Ntozake Shange’s choreopoem, for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf.

When we talk about design thinking as a human-centered methodology, I get a bit uneasy. “Human-centered” sounds like it could be done alone—since I am a human, I could center myself, and through empathy, have the ability to divine universal, human-centered solutions. Sandy Speicher, the CEO of IDEO, identifies why this is concerning: “Imagination is not neutral—what we can imagine is defined through the experience we have had which is designed through the bodies we hold which connects to the skin that we have.”

Raja Schaar, industrial designer and educator, expands on Speicher’s point about positionality and provides an essential tactic for mitigation:

Humility needs to be part and parcel of this first step. As much as I can say, “there are a lot of ways in which empathy is not enough,” I do think that teaching a level of humility might be another way of approaching your approach to design and the people that you are working with [...] Even if you identify similarly to the people you are working with, there’s still a lot of things to unpack in terms of identity which really make true empathy possible.

While empathy is an important human-centered tool, we must recognize and actively mitigate its limitations and the limitations of our own imaginations through co-creation and humility.

Pipe Cleaner Pedagogy

When I facilitate the “Yes, and” principle in design thinking workshops, I begin by giving everyone a pipe cleaner. Yes, a pipe cleaner—as in a 12” piece of highly pigmented, superbly bendy, fuzzy joy.

I take one myself, fashion it into a part corkscrew, part zigzag shape, and announce that this will be passed around and that each person should connect their pipe cleaner in whatever means and whatever shape they see fit.

I speak about the roots of “yes, and” in improvisationviii and stress the importance of recognizing the gift given to you by others and letting that gift inspire you to offer your own; the pipe cleaner sculpture grows as it is passed from participant to participant. Once everyone has added their pipe cleaner, I walk it around to let everyone admire the communal work. I then ask, “What would happen if I cut one of these pipe cleaners?” There are exclamations of, “No! Don’t!”

I cut the sculpture.

A section of tangled, multicolored, furry wires fall to the floor.

Many gasp, some clasp their hands over their mouths.

I don’t typically script facilitations, but I keep this content quite consistent: “Every idea presented is an opportunity for you to foster community and inclusivity by saying, ‘yes, and.’ When we say, ‘no,’ or ‘that won’t work,’ or ‘we don’t have the budget,’ we’ve done more than comment on that specific idea. Look at the pipe cleaners on the ground—we have lost far more than the one that was cut. We also lost everything that came after it. And more than that, we have broken trust and community with the bearer of that idea, and possibly many more of the people in that group, and maybe even ourselves.”

Prioritizing diversity, equity, and inclusion is a commitment to our collective liberation. It happens in commonplace moments, like when you respond to an idea in a brainstorming session, and in more “official” efforts, such as the words of a polished statement and action plan on your unit’s website. We have an infinite amount of opportunities to make human-centered choices each day, and embracing these will allow you and those around you to be more free.

Conclusion

Tracing more threads in the genealogical fabric of design thinking and human-centered methodologies is a crucial “yes, and” to dominant characterizations of their origins and will enrich our understandings of these heuristics. We should also apply this to what we consider to be design and who we identify as designers:

How might we situate design thinking expertise among queer, Black, feminist, and/or Indigenous communities?

The Black Lives Matter Foundation, Inc (BLM) is a global example of design thinking. Co-founders Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi began BLM as a hashtag in 2013 and have maintained a decentralized, co-created, iterative movement for creating change. It is designed to invite use, participation, and co-creation; it is non-linear, non-hierarchical, and non-prescriptive. This design maximizes access, with estimates of 26 millionix participants imbued with creative confidence and welcomed to iterate. The name/hashtag feels like the result of why laddering, as it distills and identifies the core wicked problem: Black lives are not treated as though they matter. The capacious and adoptable design embraces ambiguity and welcomes collective intelligence and a bias for action.

The Black Lives Matter movement is often characterized in news media and by politicians as chaotic, destructive, and violent, aligning BLM with racist stereotypes of Black people as impulsive and dangerous criminals. If we reject white supremacist ontologies and ascribe agency,x BLM practitioners are intentional and skilled designers. If we truly embrace design thinking mindsets, BLM is a rich example of design thinking in action—one which is fueled by social justice and crafted to maximize inclusion.[xi]

Design thinking is a tool for innovation because it is a mode of communal liberation. Let’s be intentional about how and where we situate expertise, the histories we choose and rehearse, and pairing empathy with humility. Since human-centered methodologies are antithetical to the tenets of white supremacy, we must embrace the perpetual need to recommit ourselves to these mindsets.

Design thinking gives us the ability to be free—if we do the work.

Special Thanks

I wish to thank the following, who have been co-conspirators as I have worked on these ideas in various forms: Nada Dorman, Tamie Glass, Caroline Heywood, Xie Maggie Hill, Edgardo Irizarry, Sameera Kapila, Michaela Newman, Julie Schell, kt shorb, Clarissa Smith, Yma Revuelta, and Vanessa Riley. I also want to thank some of my teachers: Charles Anderson, Daniel Banks, Sharon Bridgforth, Isaac Gómez, Ann Haugo, Daniel Alexander Jones, Kaitlyn B. Jones, Omi Osun Joni L. Jones, Kareem Khubchandani, Tim Miller, Zell Miller III, Monique Mojica, madison moore, Elizabeth Reitz Mullenix, Fiona Ngô, Mimi Nguyen, Deborah Paredez, Eric Pritchard, Rudy Ramirez, Matt Richardson, Sidney Monroe Williams, Jesús I. Valles, Christine Wong, and Kristina Wong.

Read more from the Journal of Design and Creative Technologies

References

About. (2020, May 22). Retrieved September 22, 2020, from https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/

Anderson, A. & Banks, D. (2020, June 4). Daniel Banks: Troubling the “single story.” American Theatre. https://www.americantheatre.org/2020/06/04/daniel-banks-troubling-the-s…

Black Lives Matter. (2020, September 19). Retrieved September 22, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Lives_Matter

Bridgforth, S., Jones, O.O.J.L., & Moore, L.L. (Eds.). (2010). Experiments in a Jazz aesthetic: Art, activism, academia, and the Austin Project. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Brown, J. (2008). Babylon girls: Black women performers and the shaping of the modern. Durham: Duke University Press.

Burton, J., Bradshaw, B., Harrington, C., Schaar, R., & Tunstall, D. (2020, June 27). Design education panel. Where are the Black Designers? conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_zXRlaGJQ-w&t

Carroll, A., Cunningham-Cameron, A., Gay, R., Livaudais, C., Lopez, E., Walters, K. (2020, June 27). What’s next? Roundtable. Where are the Black Designers? conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QprO27Q-Umo&t

Cherry, M. Where are the Black Designers? (2015, March 14). SXSW Interactive. https://www.aiga.org/where-are-the-black-designers-sxsw

Coleman, K., Harris, C., Joseph, P., & McMahon, S.. (2020, August 27). Reimagining public safety: Justice, equity, and anti-racism [Roundtable]. Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AbaPJCtkiqI

Du Bois, W., & Edwards, B. (2007). The souls of Black folk W.E.B. Du Bois: edited with an introduction and notes by Brent Hayes Edwards. Oxford University Press.

Herstory. (2020, May 22). Retrieved September 22, 2020, from https://blacklivesmatter.com/herstory/

Jones, O.O.J.L. (2008). 6 Rules for allies [Keynote]. Abriendo Brecha VII & The Seventeenth Annual Emerging Scholarship In Women’s and Gender Studies Conference. https://vimeo.com/78945479

Miller, C. D. Black Designers: Missing in Action. (1987) PRINT. https://www.printmag.com/design-culture/black-designers-missing-in-acti…

Newman, V., Austin, N., Lindsay L. & Oku, M. (2020, June 27). Design 2 divest / Allyship panel. Where are the Black Designers? conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zBR03h-_eMg

Noel, L. A. (2019). A Designer’s critical alphabet [Card deck]. Etsy. https://www.etsy.com/listing/725094845/a-designers-critical-alphabet

Okun, T. (2016). White supremacy culture. Dismantling Racism workbook. https://www.dismantlingracism.org/uploads/4/3/5/7/43579015/okun_-_white…

Schaar, R. & Speicher, S. (2020, June 27). Q&A with Sandy Speicher. Where are the Black Designers? conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwZVzIvKdD0

Shange, N. (2010). For colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf. New York: Scribner.

Uose, Hanna Thomas. (2019, September 3). Why don’t we call Agile what it is: Feminist. Medium. https://medium.com/@Hanna.Thomas/why-dont-we-just-call-agile-what-it-is…

i Organizational consultant Hanna Thomas Uose argues the connection between feminist practices and Agile, the design-thinking-aligned project management methodology, in “Why Don’t we Just Call Agile What It Is: Feminist” (2019).

ii The Where are the Black Designers virtual conference took place on June 27, 2020, featured 17 speakers, and over 10,000 people attended the event. It took its title from Maurice Cherry’s 2015 SXSW presentation and extends the project of Cheryl D. Miller’s 1987 article, “Black Designers: Missing in Action.”

iii I am using these terms as they are defined in Lesley-Ann Noel’s (2019) card deck, “The Designer’s Critical Alphabet.” I also used the reflection questions on the cards to solidify and unify this piece: “What is the perspective of marginalized people on the work that you are doing? How does your design work shift power? Who does your work shift power to? How does your work do this? [...] How is your work transformative?”

iv I do this because I believe in what Omi Osun Joni L. Jones states in “6 Rules for Allies”: “Supporting alternative possibilities is the only way we can all dream ourselves into the world we want to live in” (2010).

v This resource is the result of the work of many experts and decades of trainings, organizing, activism, and collaboration; please see the source for a more complete genealogy.

vi Daniel Banks (2020), director and co-founder of DNAWORKS theatre ensemble and Hip Hop Theatre scholar, often talks about the importance of the cipher. When asked about how he approaches directing, he said, “I wanted to be in a cipher, a creative circle with an ensemble, facilitating a generative process, rather than the sole voice directing people.”

vii Read more about this form in Experiments in a Jazz Aesthetic: Art, Activism, Academia, and the Austin Project (2010).

viii The emphasis of “and” as opposed to “or” is also a tactic of feminist and intersectional methodologies.

ix This number comes from the Wikipedia page on BLM; the BLM website lists the number of chapters, but not participants.

x The main project of Jayna Brown’s (2008) Babylon Girls: Black Women Performers and the Shaping of the Modern is to treat Black female performers as agential subjects “engaged in multiple directional strategies of perception” (17). For ten years, this book has reminded me to question where and when we ascribe agency and expertise.

xi The “Herstory” page of the BLM site states, “[BLM] is adaptive and decentralized, with a set of guiding principles. Our goal is to support the development of new Black leaders, as well as create a network where Black people feel empowered to determine our destinies in our communities.” The “About” page of the BLM site states, “We affirm the lives of Black queer and trans folks, disabled folks, undocumented folks, folks with records, women, and all Black lives along the gender spectrum. Our network centers those who have been marginalized within Black liberation movements.”